December 1, 2004.

The following article is based, in part, on an e-mail discussion between various members of the International Boxing Research Organization in 2004.

If it could ever be proven that Jack Dempsey’s gloves were loaded on the night he won the heavyweight championship from Jess Willard it would seriously tarnish his legacy. Likewise, if it could be shown that the beating was legitimate it should remove all doubt from the nay Sayers and cement Dempsey’s legendary status as an all time great. The Willard fight was the “Manassa Mauler’s” peak performance and his most impressive fight. There are three possibilities that have been bandied about concerning this bout:

We will examine all of the details, available evidence and the conspiracy theories concerning these possibilities. But first lets take a refresher with a little background information on the Willard-Dempsey championship fight.

Jack Dempsey earned a shot at the heavyweight title by going on a rampage through the division besting considered contenders Gunboat Smith, Carl Morris, Fireman Jim Flynn, Bill Brennan with an 18-second kayo of Fred Fulton being the most impressive. With his manager Jack Kearns, a fast- talking, swindling, fight man campaigning on his behalf, Dempsey was finally granted a shot at champion Jess Willard by promoter Tex Rickard.

The fight was held on a hot July 4, 1919 in Toledo, Ohio. Jim McDonald of San Francisco erected the stadium called, “The greatest stadium ever built” by a reporter for the New York Sun. The stadium cost 100,000 dollars in 1919 and could seat 80,000 There was one flaw however, the wood was made of fresh pine and it was so hot that the wood swelled and oozed sap. The top concession sellers were water at 15 cents a cup because of the heat and seat cushions so men would not soil their suits on the seeping wood.

Many observers thought the fight would be a mismatch. Willard was the betting favorite against the smaller Dempsey; one source indicated that on the eve of the fight Wall Street brokers made Willard a 17-5 choice. The 1965 Ring Record Book (p 759) gives odds of 6-5 Willard. The July 4, 1919 NY Times reported that the betting was 5-4 Willard at Toledo. There was much gambling going on and different bookies were no doubt offering various odds. Promoter Tex Rickard, for one, thought the 6’ 1” 187 pound Dempsey might be killed against the giant and balked at making the match, but gave into the publics demand for Willard to defend his title. Dempsey was considered by some to be just too small to have a chance against the giant Willard. Jess was huge, not so cut or chiseled, not so finely trained perhaps, but huge! At 6’6 ¼”, 245 pounds, and with a reach of 83” he was, with the exception of Primo Carnera, the largest man to hold the heavyweight championship until the likes of Lennox Lewis and Vitaly Klitschko. Willard had assets other than size; he had a good long jab, proven stamina (going 26 rounds and maintaining a knockout punch when he won the title against Jack Johnson), a tough chin as he had never been knocked off of his feet, and punching power, breaking the neck of Bull Young with an uppercut.

The champion knew of Dempsey’s penchant for rushing across the ring and attacking his foes with a hell bent attack. Dempsey came into this fight with five knockouts in five months all in the first round. Willard had a plan for facing Dempsey, “He’ll come tearing at me, but I’m seventy, eighty pounds heavier than the boy. I’ll have my left out. He’ll have to watch for my left when he’s tearing in at me. Then I’ll hit him with a right uppercut. That will be the end.”

In the ring Dempsey looked tiny next to the massive Willard. Rex Lardner wrote, “A couple of fans seeing Dempsey eye Willard, nudged one another and said, “Look, the big guys got him buffaloed already.” But Dempsey, with his killer’s eye, was appraising Willard not as a danger, but as a target – that long body easy to hit, that sizeable jaw, those arms that could not push you away once you got inside. Would the jab of a thirty-seven year old man who did not relish fighting stave off a stalking, weaving, hungry, hooking challenger?” When they met in ring center Dempsey stared at the ground, refusing to look up at his towering opponent, shades of Leonard-Hearns?

“More suspicion than is usual surrounded the arrangements for the Dempsey-Willard fight,” wrote Lardner. Why this was so one can only guess. Was there some reason not to trust Dempsey or Kearns? Jess and his people wanted the bandaging of hands to be done in the ring, or in the presence of members from the other camp, and he got his way. The films clearly show Dempsey entering into the ring without gloves. This brings us to the first possibility. Were Dempsey’s hand wraps loaded with plaster of paris?

Jack Kearns, Dempsey’s manager, came out with his “confession” in the January 13, 1964 Sports Illustrated, in an article titled, “He didn’t know the gloves were loaded.” The SI story noted that Kearns was a “wily trickster and a ruthless opponent when money was involved.” In his confession Kearns said the following:

“I had bet $10,000, which we could not afford to lose at 10-1, that Dempsey would win in the first round. If he did we would make a $ 100,000 –equivalent to Willard’s guarantee and substantially more than our own $27,500 guarantee. I had schemed and connived for too many years to let anything go wrong with a bet like that, let alone with the championship of the world. The hell with being a gallant loser I intended to win.”

“My plan had to do with a small white can sitting innocently among the fight gear on the kitchen table. I poured myself a nightcap and picked up the can, grinning at the neat blue letters on its side. All it said was “Talcum Powder”…I had bought another can of powder. This one was labeled “Plaster of Paris”…I placed the plaster of paris into the talcum powder can and replaced the lid. Set back among the fight gear –the bandages, the Vaseline, the razor blades, the cotton –it looked as innocent as any of them.”

A witness to each camp was to observe the bandaging of hands as insurance against any shenanigans. Willard’s, chief second, Walter Moynahan was in Dempsey’s dressing room to observe the proceedings.

According to Kearns this is how he loaded Dempsey’s gloves, “I quickly wound on Dempsey’s bandages under Moynahan’s vigilant inspection. After I finished with the wrappings I turned to Jimmy DeForest, my trainer, and pointed to the water bucket. “Give me that sponge well soaked with water”, I ordered, “I want to keep the kids hands cool.” The sponge, dripping with water, made a sloshing sound as I clamped it to the bandages on Dempsey’s hands. In a moment they were drenched through. “Now the talcum powder,” I directed DeForest, and he passed me the innocent looking can. I sprinkled the contents heavily over the bandages.” Moyhanan made no comment. Dempsey, who was entirely innocent of what had happened, stood there in almost a stupor. I had to smile as a call came to enter the ring.”

That is how Kearns said he loaded Dempsey’s gloves without the fighter knowing anything about it. But is such a thing possible? One must first ask is it possible for Dempsey to have entered into the ring without gloves, which the film and still photos clearly prove, and the referee and principles not noticing the hardening substance on his hand wraps? More importantly is plaster of paris a good and efficient way to load a pair of gloves?

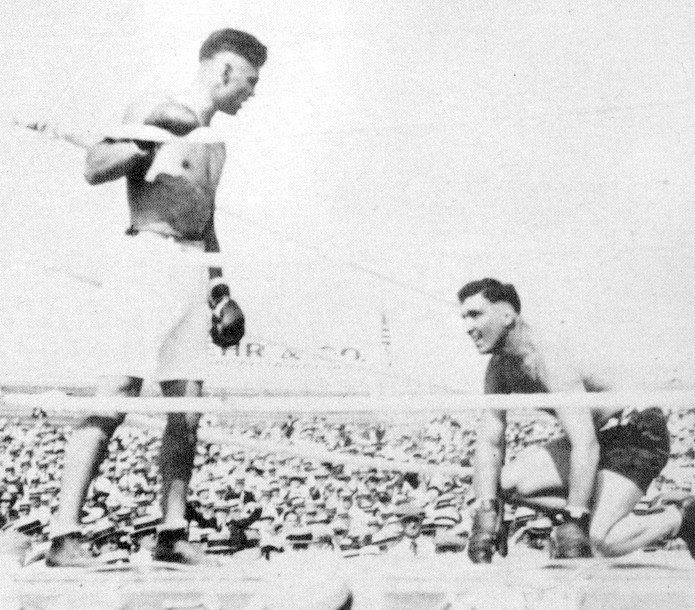

Boxing Illustrated conducted an experiment to test whether it was possible to use plaster of paris successfully under fighting conditions. The results were reported in the May 1964 issue of BI, pp 20-24, 66. Hugh Benbow and Perry Payne (manager and trainer of Cleveland Williams) used plaster of paris on Cleveland's hands and reenacted what Kearns said occurred in Dempsey's dressing room. After 35 minutes of toasting to reenact the 114-degree heat of Toledo that day, Cleveland Williams hit the heavy bag five times. Benbow examined the wraps and found that the plaster had cracked and crumbled. "This stuff." said Cleve, "wouldn't do anybody any good."

The Boxing Illustrated test proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the plaster of paris would not have held up after the first punch, it would have crumbled and left chunks in his mitts and every punch thereafter would have been quite painful and there is little doubt he would have broken his hands. The inventor of the product issued a statement as to the impossibility of using plaster of paris without breaking all the bones in the hands. Dempsey’s hands were not broken and he continued to punch with authority with both hands. This alone dispels the idea that Dempsey’s gloves were loaded with plaster of paris.

Note the mess on Williams hand in duplicating the conditions of Kearns confession.

Note the mess on Williams hand in duplicating the conditions of Kearns confession.

Dempsey July 4, 1919. No plaster of paris on his handwraps.

Dempsey July 4, 1919. No plaster of paris on his handwraps.

Teddy Hayes, one of Dempsey's seconds, said he was the one who cut off Dempsey's gloves, not Kearns. "I snipped it right in front of a whole milling crowd in the dressing room. Don't you think if there was plaster of paris, Kearns would have been there, standing guard? And you can't cut off plaster of paris with scissors. I would have to have had a hacksaw." -A Flame of Pure Fire p 98.

Nat Fleischer, later founder of Ring Magazine, was an eyewitness reporter, and related the incident in 50 Years at Ringside, “That question has been discussed time and again by persons incapable of giving a proper answer except through hearsay. I watched the crumbling of the “Pottowatomie Giant”, and after the terrible beating that Willard took, I heard too the many remarks that no human being could deal out so much punishment with padded mitts unless there was something hidden in the gloves. I was at the fight. I saw Jimmy Deforest, Dempsey’s trainer tape Jack’s hands. I watched every move of the men in Jack’s quarters. I think I can clear the atmosphere once and for all with an accurate version of what happened. Jack Dempsey had no loaded gloves, and no plaster of paris over his bandages. I watched the proceedings and the only person who had anything to do with the taping of Jacks’ hands was Deforest. Kearns had nothing to do with it, so his plaster of paris story is simply not true. Deforest himself said that he regarded the stories of Dempsey’s gloves being loaded as libel, calling them “trash” and said he did not apply any foreign substance to them, which I can verify since I watched the taping. It was the 4th of July, it was very hot and he did pour some water on his hands when Jack complained of the heat and that hardened them, but that was all that was done. Kearns began trashing Dempsey after they had a falling out, and that’s all there is to it.”

Historian J.J. Johnston puts the nail in the coffin of the plaster of paris theory with the following observation, “The films show Willard upon entering the ring walking over to Dempsey and examining his hands. That should end any possibility of plaster of paris or any other substance on his hands.”

Major Biddle’s Marine Corp marching band performed a bayonet exhibition in ring center before the start of the heavyweight championship and tore up the canvas with heavy boots. A new canvas had to be installed before the main event. When the new canvas was laid, a workman tied a rope around the bell hampering the string that sounded the start of the round; this delayed the beginning of the fight. It would also play a role in the outcome. The timekeeper was Warren Barbour, later to become a U.S. Senator from New Jersey. He had a stopwatch in his left hand and the bell cord in his right. He started the stopwatch when he pulled the bell cord, but the bell did not sound. He pulled it again and still there was no sound. He was handed Major Biddle’s whistle and used it to hit the bell and the round started. Precious seconds ticked off. At the end of the first round after the seventh knockdown Willard was declared saved by the bell by the timekeeper who had forgotten his watch was off time! Dempsey should have won by a knockout in the first round!

When the bell finally rang for the opening round Dempsey did not charge at Willard like the champion expected. Roger Khan wrote, A Flame of Pure Fire, “He came forward lightly on the balls of his feet, circling left, then right, bobbing, circling, shoulders rolling, and moving his head. Twice Willard shot his long left toward Dempsey’s face. Neither made much of an impact. Dempsey was keeping his chin tucked underneath his left shoulder. Jack quickly stepped in and landed a right to the heart. Then he forced a clinch tying up the big mans arms. With Dempsey’s left glove clamped on the inside of Willard’s right elbow the giant could not unleash his lethal uppercut.” This inside clinching tactic was later used on occasion by Mike Tyson, whose ring idol was Jack Dempsey. The referee forced a break and Willard raised his gloves high to show he was breaking clean. Dempsey continued to circle waiting for an opening. The “feeling out” process continued through the first minute of the fight.

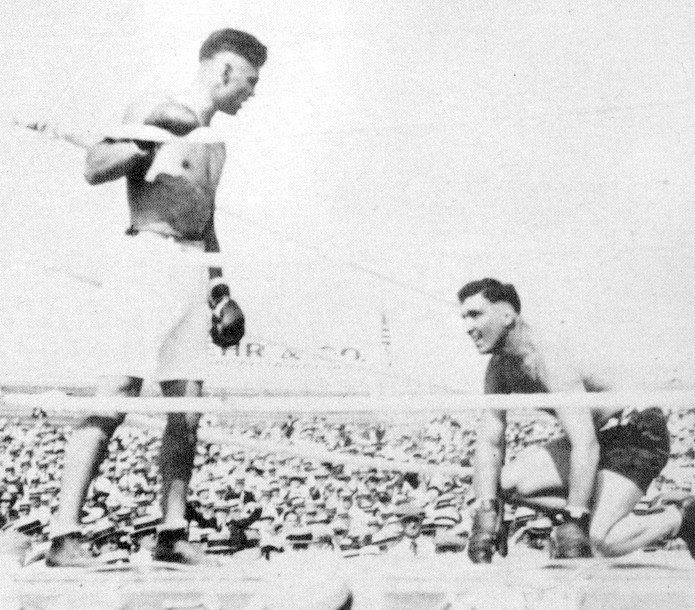

Dempsey circled left, bobbed and circled to Willard’s right. Willard pawed with his left and then it happened. Dempsey slipped under the jab and turned a left hook that slammed into Jess’s mighty jaw. Dempsey followed up with a torrent of blows, a right, a left hook to the body, a short right to the mouth and a full whirl powered left hook to the cheekbone. This final left hook was a terrific blow. It was this punch more than any other that brought on Willard’s defeat. Lightweight champion Benny Leonard wrote, July 5 NY Herald, “A left hook perfectly timed, accurately placed and powerfully delivered won the heavyweight championship for Jack Dempsey this afternoon.” Willard crumbled to the canvas, going down for the first time in his career, and the onslaught was on. Six more times Willard would hit the canvas in the first round.

Dempsey circled left, bobbed and circled to Willard’s right. Willard pawed with his left and then it happened. Dempsey slipped under the jab and turned a left hook that slammed into Jess’s mighty jaw. Dempsey followed up with a torrent of blows, a right, a left hook to the body, a short right to the mouth and a full whirl powered left hook to the cheekbone. This final left hook was a terrific blow. It was this punch more than any other that brought on Willard’s defeat. Lightweight champion Benny Leonard wrote, July 5 NY Herald, “A left hook perfectly timed, accurately placed and powerfully delivered won the heavyweight championship for Jack Dempsey this afternoon.” Willard crumbled to the canvas, going down for the first time in his career, and the onslaught was on. Six more times Willard would hit the canvas in the first round.

The July 5, 1919 New York Herald sports page headlined, “Jack Dempsey Whips Willard in Three Rounds. One Punch Practically Deciding the Battle.” Lightweight champion Benny Leonard writing for the Herald also noted “Left Hook to Jaw With Terrible Force Takes Fight Out Of The Champion.”

Willard was counted out at the end of the first round and Dempsey was rushed out of the ring a victor. But the timekeeper, forgetting that he had started his watch before the bell, told the fight’s referee Ollie Pecord that the round ended before Willard was counted out. Dempsey was forced to come back and continue fighting or be disqualified. He did not knock Willard down again, although Willard was beaten so badly he could not come out for the fourth round.

In The 12 Greatest Rounds of Boxing pages 17-18, “The Fight Doctor”, Ferdie Pacheco, writes, “The damage was indeed severe. In the first round Willard’s zygomatic arch (cheekbone) was shattered in 12 places. In the same round the champion sustained a broken nose, a jaw that was broken in 13 places, and 8 avulsed teeth. In addition to facial fractures he suffered 2 fractured ribs.”

Likewise Dan Daniel wrote, Aug 1979 Ring Magazine, "Blood was flowing from Willard's mouth. Two front teeth had found their way to the canvas. His right eye had begun to close and the right side of his face was swelling abnormally. He looked as if he had been struck with a blackjack."

Let’s not jump to conclusions but slowly examine the available evidence. It certainly is possible for human beings to inflict heavy damage upon one another in a boxing match. Mike Tyson in his fight with Andrew Golota busted him up pretty badly in their fight. Golota suffered a broken eye socket, a broken jaw, and a busted eardrum. The tremendous power generated by men such as Jack Dempsey and Mike Tyson can definitely shatter bones. Consider also that Dempsey was using Sol Levinson 5-ounce gloves and his bandages were soaked in water making them tighter. This alone is very brutal. The question here isn’t the type of damage Willard sustained. It’s the amount of damage. Dr. Pacheco stated, “I have been a physician in boxing for 40 years and I have never seen such anatomical damage as Jack Dempsey inflicted on Jess Willard.”

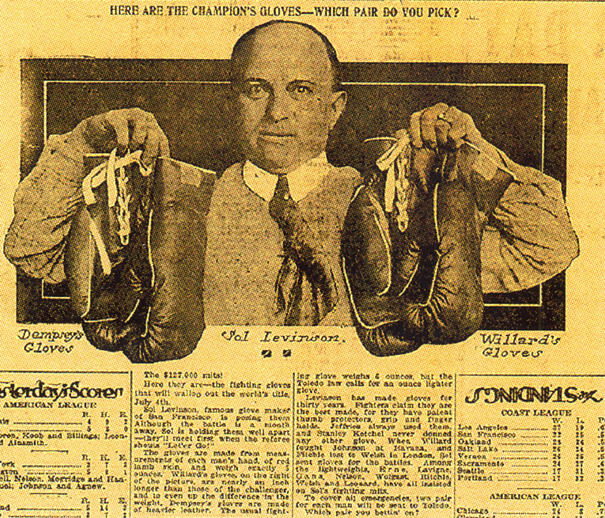

The 5-ounce Sol Levinson gloves used by Dempsey and Willard in Toledo.

The 5-ounce Sol Levinson gloves used by Dempsey and Willard in Toledo.The question is the amount of damage that Willard sustained. If Willard did receive the tremendous amount of injuries that Dr. Pacheco and Dan Daniel write, then it would seem very likely that Dempsey’s gloves were loaded. Many of these modern reports are often not in agreement. There are very good reasons to question these so called medical reports as we shall see after awhile.

The second possibility that has been suggested is that Dempsey held a railroad spike or an iron bolt in his left mitt. What evidence, if any, suggests that Dempsey may have held an iron spike in his glove?

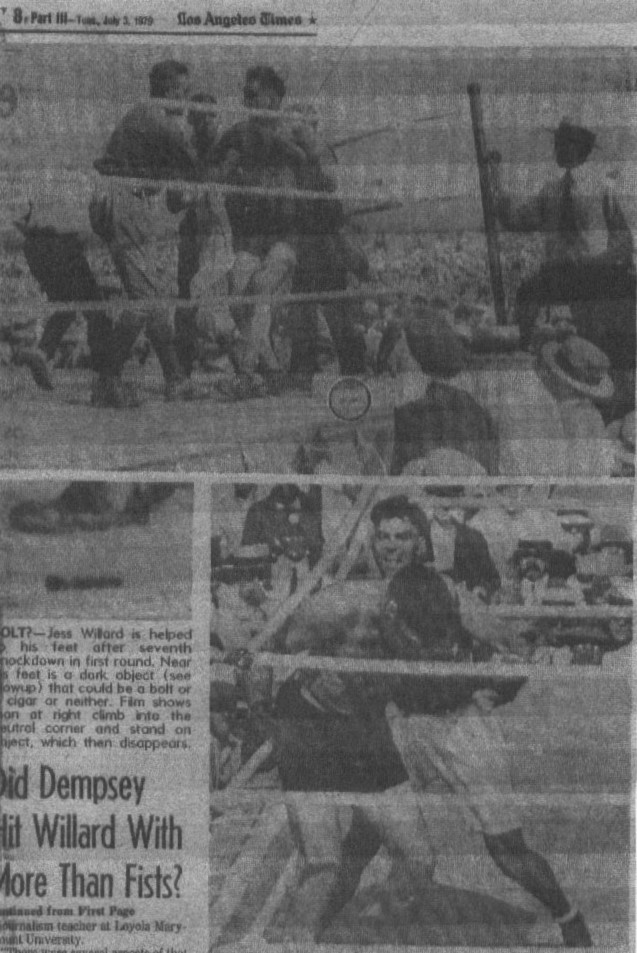

In the July 3, 1979 Los Angeles Times, Joe Stone a boxing historian, and former referee states that he is convinced that Dempsey carried an iron bolt in his left hand. “There were always several aspects about that fight that bothered me,” said Stone. But it wasn’t until he was studying still photos of the fight that he began to believe that Dempsey held a load in his left glove, due to a dark cigar shaped object that can be seen on the ring canvas.

Joe Stone says he’s convinced for several reasons, but mostly because of a peculiar incident than can be seen on the film during and after Willard’s seventh knockdown in round one. While Willard sits dazed in a neutral corner, a cigar-shaped dark object can be seen on the ring apron next to his left knee.

1979 LA Times piece. Is it a cigar? Or is it a bolt?

1979 LA Times piece. Is it a cigar? Or is it a bolt?

“Now watch this,” Stone says, viewing the film of the fight. “Look at this guy.” He points to a man walking from the area of Dempsey’s corner to the spot where Willard had just arisen. While Dempsey’s handlers are jumping up and down for joy in the ring, this fellow climbs into the ring at the neutral corner. He stands directly over the dark object on the apron. A fan stands covering the view of the man’s feet. But after a few seconds, he walks away, the fan sits down and the dark object is gone.

“See that?” Stone said. “I think he kicked it off the apron, “I think Dempsey had a load in his glove.”

Stone says there are five very peculiar things about this fight. These are:

Did Dempsey use an iron bolt in his left glove? As Stone points out if one assumes it is then it does explain a lot about some of the alleged circumstances concerning this fight. But, there are other points to consider not addressed by Stone in his analysis. Let’s assume, for point of argument, that it is not a bolt, but a cigar lying on the canvas. It is certainly shaped like a cigar. There are a good number of fans standing right up at that corner. It seems just as plausible that a fan may have tossed his cigar in the ring. It seems a little curious, perhaps suspicious, but it doesn’t prove that Dempsey was carrying a load. No one can say for certain by looking at the film and still photo’s of the fight what that object is. Let’s give Dempsey the benefit of the doubt for the moment and examine some more facts surrounding this case.

The first thing one discovers when putting this theory under the microscope is that the extent of Willard’s reported injuries have been greatly exaggerated. The report quoted by Pacheco and a few others, is based off a medical report by a man who was not a licensed physician! A reputable physician did not examine Willard after the fight.

Arly Allen who is writing a book on Jess Willard supplied the following Kansas newspaper reports:

A statement was issued after the fight by Jim Byrne "official physician to a local athletic club in Toledo" that Willard had a dislocated jaw, a fractured cheek bone and several "mashed" ribs and that it would be "at least six weeks before Willard is back to normal condition and can move comfortably." This was reported in the Kansas City Times July 8, 1919, p. 10 "Willard's Jaw Dislocated.”

Pacheco and other reporters based the extent of Willard’s injuries off of this widely distributed report by Byrne who was not a physician. However it soon turned out that Jim Byrne was not a doctor, but was rather a "rubber" in a bathhouse in Battle Creek, Michigan. According to the reporter in an article, "Willard's Jaw is All Right," Kansas City Star, July 8, 1919, p.11, Byrne "doesn't know a nickel's worth about the human anatomy."

Other reports also make it clear that Willard was not as severely injured as has been claimed. An interview by a reporter from Kansas City on July 5, 1919, "Jess Refuses to Alibi," Kansas City Star, July 6, 1919, p. 14, the day after the fight, showed that "aside from the swelling on the right side of his face, which is under cold applications, he was none the worse apparently for his encounter with Dempsey."

In an interview on July 7, the Kansas City Times announced that Jess and his wife were leaving Toledo and driving their car back to Lawrence, Kansas that day. His condition seemed to be fine. "The swelling over his left eye had entirely disappeared and the only mark he bore was a slight discoloration over the eye and a cut lip." ("Willard starts for Home," Kansas City Times, July 8, 1919, p.10).

Another reporter interviewed Jess in Chicago on his way home. "Hello, Jess" said the reporter, "How do you feel ?" "Hello," said Willard, "I'm feeling great. Would you like to spar a few rounds ?" (Kansas City Star, July 10, 1919, p. 10).

Later, according to a reporter for the Topeka Daily Capital, July 16, 1919, p. 8, who interviewed Jess when he got back to Lawrence, "The ex-champion didn't have any black eye, nor any signs that he was injured in any way."

If one's jaw was broken in 13 places it would be practically impossible to speak and give a post fight interview. But Willard clearly did. The July 5, 1919 NY Times quotes Willard as saying, "Dempsey is a remarkable hitter. It was the first time that I had ever been knocked off my feet. I have sent many birds home in the same bruised condition that I am in, and now I know how they felt. I sincerely wish Dempsey all the luck possible and hope that he garnishes all the riches that comes with the championship. I have had my fling with the title. I was champion for four years and I assure you that they'll never have to give a benefit for me. I have invested the money I have made." Willard not only gives a lengthy interview but refers to his condition as only "bruised" and says he had put others in the same conditon he was in.

Joe Chip, who rode with Willard in a car back to their camp after the fight, backs up the fact that the extent of Willard’s injuries is not so severe as has been reported. Chip said, July 5, 1919 Youngstown Telegram, "Willard was not beaten up so badly. His right jaw was pretty well bunged up but not broken. His right eye was closed and his stomach was red, but this was nothing. He lost no teeth and so far I did not see anything about his condition to warrant the services of an ambulance -even though he was whipped to a frazzle."

A couple days later Chip reaffirmed his statement, July 7, 1919 Youngstown Telegram, "The report that several teeth had been knocked out is untrue. Jess was cut in the lip, also under the right eye. Dempseys body punches did no harm."

Historian Steve Compton who submitted the Youngstown, Ohio reports commented, "The only people who ever said anything about Willards injuries knew nothing about the fight. Chip wasnt a friend of Willards and other than being an employee for the duration of the fight he had no other ties to Willard. I have never seen a contemporary account by anyone from the Willard camp as to the severity of his injuries which have become commonly quoted today. Joe Chip was a sparring partner for Willard, and other than that had no relationship whatsoever to Big Jess. The statements were all made within days of the fight."

All of these reports seem to contradict the common modern descriptions of Willard having lost 6-8 teeth, suffered multiple jaw fractures, a fractured eye socket, a broken nose, and broken ribs.

There are very good reasons to doubt that Dempsey was holding an iron load in his glove, besides the false and exaggerated “medical” report. These are best summed up by historian Stan Smith who makes the following observations, “I pulled my 16MM film of the fight and in the first part of round one, before the first knock down, Dempsey moved around the ring with open gloves. The spike would have made a hell of a clunk when it hit the ring floor. He also used open gloves, with both hands; on Willard’s arm to push him out of clinches. After the first knock down Dempsey held the top rope with his left hand and after one of the other knockdowns he did the same with his right hand, so much for the iron-spike theory.”

Historian Eric Jorgensen adds, “Kearns goes to all the trouble to concoct a phony story about plaster of paris in an effort to discredit Dempsey instead of just telling the truth about the iron bolt? How much sense does that make? Zero.”

It seems highly unlikely, indeed virtually impossible, that Dempsey could have dropped an iron load out of his left hand, in the presence of ringsiders, and kept it held in his hand throughout the first round given his actions in the ring. How could Dempsey have held an iron spike in his hand with ringsiders and veteran boxing observers such as lightweight champion Benny Leonard, Nat Fleischer, Damon Runyon, and Ring Lardner not being able to see it? How could he have held an iron load of that size in his hand and the referee, who came in close enough to break clinches and even grabbed Dempsey by the arms and pull him back, not see it? How could Dempsey be holding an iron spike in his left hand when his hand is grabbing the ring ropes after the first knockdown? How could he push Willard in the clinches with open gloves if he had something in his hands? How could Dempsey grip Willard’s right arm at the elbow to keep him from throwing an uppercut if he held something in his hand? The answer to all of these questions should be obvious. Quite simply he couldn’t.

As to why Dempsey didn’t floor Willard again after the first round one must recall it was 114 degrees in the ring that hot July 4th day. Dempsey exerted a lot of energy in the first round. Eric Jorgensen writes, “Dempsey took Willard out in the first, then sprinted out of the ring, jumping up and down in celebration -- only to have to sprint BACK to the ring to avoid being counted out. It's not surprising at all that he was a little winded and, thus, proceeded a little more cautiously thereafter. Willard was about to go down again at the end of the 3rd, though, and would surely have done so had he made it out for the 4th.”

The major questions surrounding this controversy are answered. It has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt that Dempsey did not have plaster of paris on his hand wraps. Jack Kearns credibility was never good and he had reasons to dislike Dempsey after their falling out when Dempsey fired him during his years when he was the champion. The testimony of eyewitnesses Nat Fleischer, trainer Jimmy Deforest, and second Teddy Hayes debunk Kearns story. The Cleveland Williams/Boxing Illustrated test puts the myth to rest. The film demonstrated that it would be impossible for Dempsey to have held an iron load in his hand given his actions in the ring. The cigar shaped object was probably just that, a cigar. Cigars were very, very popular amongst men in those days and fights were often viewed through a large cloud of smoke. The 5-ounce Sol Levinson gloves, water tight hand wraps, and Dempsey’s natural punching power and inner rage were more than enough to break Willard’s jaw and cause the injuries seen by various reporters after the fight.

Jack Dempsey was simply too good of a fighter for Jess Willard to deal with. Legendary sportwriter Damon Runyon, penned in the July 5, 1919 Chicago Herald and Examiner that the fight was "Like a Tiger Mauling an Ox." Benny Leonard, who was known to be able to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of opponents as well as anyone, rightly picked Jack Dempsey to win the heavyweight championship from Jess Willard in the July 3, 1919 NY Herald. He gave the following reasons:

In conclusion we must give credence to the third possibility, and agree with eyewitness Nat Fleischer, who said, “Jack Dempsey had no loaded gloves, and no plaster of paris over his bandages.” The bottom line is that the complete film shows Willard checking Dempseys wraps when he entered the ring. So much for the plaster of paris theory. Dempsey used open gloves to push in the clinches and had each hand held to a rope between various knockdowns. So much for the iron bolt theory. The myth of Dempsey having loaded gloves should be put to rest. Dempsey is an all time great heavyweight champion, an inspiration to fighters like Mike Tyson, who called the legendary fighter, “a very vicious man.” That viciousness was never more evident than on the night of July 4, 1919 in Toledo, Ohio when Jack Dempsey became the heavyweight champion of the world by using the natural punching power that he possessed.

Sources

Allen, Arly. 2004. E-mail correspondence.

Boxing Illustrated. May 1964. Were Dempsey's Fists Loaded in Toledo? By John Hollis.

Bromberg, Lester. 1962. Boxing’s Unforgettable Fights. Ronald Press Co. NY. Dempsey the Giant Killer of Toledo.

Compton, Steve. 2004. E-mail Correspondence.

Fleischer, Nat. 1958. 50 Years at Ringside. Fleet Publishing Corp. NY.

Johnston, Jim J. 2004. E-mail correspondence.

Jorgensen, Eric. 2004. E-mail correspondence.

Khan, Roger. 1999. A Flame of Pure Fire. Harcourt Brace and Co. NY.

Lardner, Rex. 1972. The Legendary Champions. American Heritage Press. Chapter 8 Dempsey The Massacre at Toledo and Others.

Los Angeles Times. July 3, 1979. Did Dempsey Hit Willard With More Than Fists? By Earl Gustkey.

Pacheco, Ferdie. 2003. The 12 Greatest Rounds of Boxing. Sport Classic Books. Toronto.

Ring Magazine Aug 1979 Dempsey Slaughters Willard by Dan Daniel.

Smith, Stan. 2004. E-mail correspondence.

Sports Illustrated Jan 13, 1964. He Didn’t Know The Gloves Were Loaded. By Jack Kearns with Oscar Fraley.

University of Illinois NEX Newspaper Library.

………………………

Other Contributors:

John A. Bardelli, Bob Caico, Jeff Cox, Dan Cuoco, Chuck Johnston, Clay Moyle, Frank Stallone, Miles Ugarkovich.