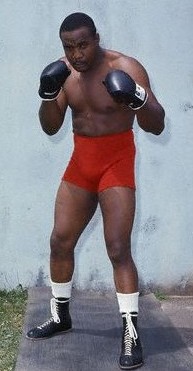

The images are mutually contradictory. One is of the single most menacing countenance boxing has ever produced, an impassive, unreadable gaze, as lifeless as that of a shark, ageless, emanating from a face that shows no hint of compassion. It is the face of the worst alley nightmare made real.

The second is of the same man, lying flat on his back, a seeming madman standing over him, screaming wildly down at his prone form.

Sonny Liston may be the least accurately perceived heavyweight champion in boxing history. For fans born before the mid-1950’s, he is often remembered as a virtually invincible monster. Those whose interest in boxing started after the ascendancy of Muhammad Ali will think of him—if they think of him at all—as the victim of two humiliating losses. And they will likely wonder why Sonny Liston was ever so highly regarded in the first place.

Sonny Liston may be the least accurately perceived heavyweight champion in boxing history. For fans born before the mid-1950’s, he is often remembered as a virtually invincible monster. Those whose interest in boxing started after the ascendancy of Muhammad Ali will think of him—if they think of him at all—as the victim of two humiliating losses. And they will likely wonder why Sonny Liston was ever so highly regarded in the first place.

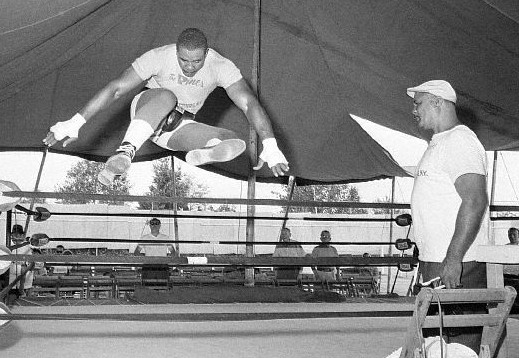

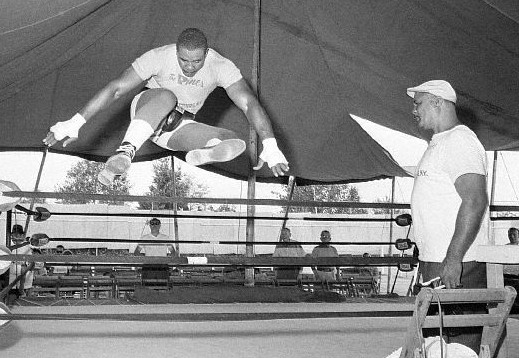

Liston was made to be a fighter. His physical attributes bordered on the freakish. At barely six-foot, one-inch, he had an eighty-four inch reach—longer than that of all other champions with the exception of Primo Carnera. His neck was a massive eighteen inches. But the number that leaps off the page—the statistic that looks initially like a typo—is that which corresponds to his hands. When closed into a fist, they measured fifteen inches around, virtually twice the size of an average man’s. To contemplate the impact of a fist that large, delivered over a distance that great, from a man so determined to do damage, would give even the bravest opponent pause.

In his first four fights, Sonny Liston fought two opponents with losing records, the first of whom had had twenty-five professional fights. Very late in his career, he fought three others. Other than on these five occasions, Liston fought only men with winning records. In his sixth fight, he ventured to Detroit to fight hometown prospect Johnny Summerlin (19-1-2). He won a decision. Less than two months later, he returned, beating Summerlin again. These wins are instructive. They show that, although mob-controlled, Sonny was never a protected fighter. His managerial chain of command—Frankie Carbo to Blinky Palermo through to the canny Willie Reddish—all knew that Sonny was the goods.

Liston lost his eighth fight on a split decision when the wisecracking Marty Marshall made him laugh and, catching Sonny with his mouth open, broke his jaw. Liston avenged his defeat five months later, knocking Marshall down four times en route to a sixth round kayo win.

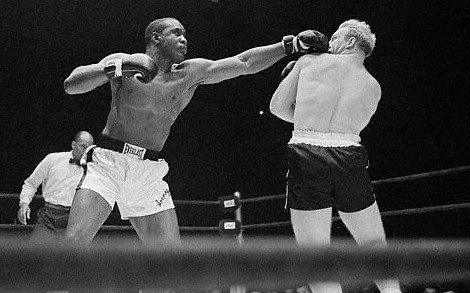

Liston’s four-and-a-half-year, thirteen-fight trajectory through the ranks to the heavyweight title and his first defense of it began in February of 1959. He decimated the top ten ratings, knocking out virtually every other fellow contender*. His opponents during this period had a combined record of four hundred nineteen wins with only ninety-nine losses. (Bear in mind that thirteen of those losses came to Liston himself.) The one-sidedness of Liston’s wins served to eliminate his victims as possible opponents for heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. Sonny had dispatched their only common opponent, Roy Harris, who’d gone twelve rounds with the champ, in less than a round.

During this period, only the talented Eddie Machen lasted the distance with Sonny, losing a clear-cut unanimous decision over twelve rounds. This fight is also instructive. It shows that, although Liston generally needed fewer than five rounds to defeat a top heavyweight, he was comfortable going twelve rounds, showing neither signs of fatigue nor loss of power.

But perhaps the fights which best exemplify Liston’s strengths are his two short contests with Cleveland Williams.

Williams was a Herculean, thunderously hard-punching heavyweight. Going into the Liston fight, he’d amassed an overwhelming 43-2 record, with all but nine of his wins coming by knockout. Everything about Cleveland Williams was impressive—his power, his physique, even his nickname “Big Cat”. His ring strategy was simple: to move forward and knock people out. Although no great technician, he stalked his prey with very fluid movement and good hand speed.

The Liston fights are misremembered as brutal affairs between two irresistible forces. The films, however, show something very different. Liston uses beautiful head movement and what may be the division’s greatest ever jab to avoid most of Williams’ punches and to keep him off balance. Williams does occasionally land with extraordinarily powerful shots, but Sonny shakes each one off. In their combined five rounds of boxing over the course of their two fights, Liston is only shaken briefly once, and never in danger of being dropped. The most astounding thing about his approach is that he is equally comfortable coming forward or retreating—which he does whenever he feels pressured. This runs entirely contrary to the perceived wisdom about Sonny Liston. Although he was a finisher of comparable stature to Dempsey, Louis, Marciano, and Frazier, he was the only member of this shark-like group who was a boxing conservative. Sonny Liston never took an unnecessary chance in the ring. Far from being a one speed, forward-moving exemplar of aggression, Liston constantly thought during fights, making adjustments, using lateral movement, and taking a step back when it suited his purpose. His hands were always held high, he threw a constant battering ram jab to keep his opponents honest, his chin was tucked in, he moved his head better than any other heavyweight champion, with the possible exceptions of Jack Johnson, Jersey Joe Walcott, and Larry Holmes, and he was always in position to fire back.

Moreover, although Ali is thought to be the harbinger of ring psychology among heavyweights, Liston was a true innovator of unsettling self-presentation. He would stuff towels beneath his hooded terrycloth sweatshirt in order to enhance his already formidable musculature. Adding a poker-faced stare, he discomfited opponents in a manner seldom seen in boxing rings before. Perhaps only a prime Joe Louis was as capable of freezing a man in his tracks before the first punch was thrown.

But, ultimately, one has to confront the issues of Sonny Liston’s two fights with Muhammad Ali. Since these reduced his title reign to one successful defense, his legacy suffers greatly, especially when compared to the number of title defenses attained by Louis, Ali, Holmes, or Lewis. I’m not sure if an already old Liston losing to a young Ali should seriously demote him in terms of overall standing.

But that doesn’t matter. Neither fight was on the up-and-up. I had a best friend in the boxing business. He is no longer living, but he was someone whose credibility, to me, was totally beyond question. He was intimately involved with Sonny Liston’s career, and he participated and benefited from both Liston-Ali fights. In a nutshell, here is what he said occurred and why:

After the second Patterson fight, there were no viable opponents for Liston. Aside from Ali, he had thoroughly destroyed every possible title aspirant. No one thought he could be beaten and, more importantly, no one was willing to pay to see him beat up anyone else.

Sonny was getting old—probably already around forty—and he had no great love for fighting. It didn’t make economic sense to have him fight an endless series of low paying title defenses for another ten years. The guys who controlled his career decided that it was better to make two huge, quick scores.

They fixed the fight in Miami. Ali never knew about it. Liston’s people bet huge amounts, getting almost eight to one odds, on Ali. Because the conclusion of the first fight was so ambiguous, Liston remained a betting favorite—at about seven to five—in the rematch. The wiseguys got to clean up twice with the same play. It’s clear that, in the second fight, Ali spotted what was going on the moment Liston went down from a non-punch. But Ali was a very quick study, and made his press release adjustments by the time he was out of the ring.

Sonny Liston was an adult and a businessman. He beat people up in order to get paid. And, in the two biggest fights of his life, he lost in order to get paid. Sonny Liston did not agonize over what his place might be in the Boxing Pantheon. He didn’t care what you thought, he didn’t care what I thought, and he didn’t give a fuck about what John F. Kennedy—who called Floyd Patterson to the White House before the his first fight with Sonny—thought. He was in the boxing business. He participated in two fixed fights of great historical importance. There were possibly a couple more later in his career—which he won—and one last fight he was supposed to lose and, for mysterious reasons, didn’t.

Unlike most boxing people, I find no fault with Sonny Liston throwing away the heavyweight championship. It was doing him no good.

Epilogue:

How good was Sonny Liston?

How good was Sonny Liston?

About ten years ago, just prior to his becoming boxing commissioner for the State of New York, Floyd Patterson and I were briefly business partners. One night, during a blizzard, we stayed up very late, drinking coffee around a roaring fireplace in the living room of his home in New Paltz, New York. Being interested in Liston, I asked Floyd who the hardest puncher he’d ever faced was. I thought I knew the answer. But Patterson surprised me.

“Ingemar Johansson.”

“But Floyd, you fought Liston twice. Ingemar Johansson?”

Floyd smiled his characteristic self-deprecating smile. “Oh, but when I fought Ingemar, I thought I was going to win.”

* - Only Ingemar Johansson and Henry Cooper, of those fighters rated in the top ten during Liston’s prime years, escaped beatings by him. Cooper’s manager was quoted as saying, “If we saw Sonny Liston coming, we’d quickly cross the street.”